- Home

- Baynard H. Kendrick

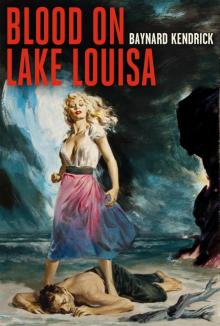

Blood on Lake Louisa Page 4

Blood on Lake Louisa Read online

Page 4

We must have driven for an hour longer. All semblance of road had long since disappeared. We were following Cass merely by the trail his car left when it crushed down the high grass and weeds which at times reached up above our headlights. I expected any minute to run into an invisible stump and end the journey permanently, but I kept on, hoping for the best.

“Do you think he knows where he’s going?” I asked.

“Sure, Doc. That cracker’s as much at home in these woods as we are in Orange Crest.”

“Have you any idea where we are?”

“Only vaguely from the county maps. I’ve searched titles for some timber lands out in this section. I think we’re skirting along the edge of Tiger Swamp, but I’m not sure.”

“Well we’ve come nearly forty miles from town and I’m getting darn tired—”

We ran into a clearing as I was speaking and Cass was standing right ahead of us waving us down. I climbed out with a sigh of relief glad of the chance to stretch myself after the arduous drive. It was not long before I was wishing myself back in the comfortable seat behind the wheel. Marvin started a vigorous battle against the mosquitoes which swarmed around us.

“Are we near there, Cass?”

“Hit’s a right smart ways, Mister Lee. We all better be agoin’.” He produced a gasoline lantern from the rear of the Ford, and lit it with some difficulty for it had to be heated first, and the breeze kept blowing out his matches. Finally the mantles flared up and the white, hard light illuminated an area of twenty feet around us. I switched off the car lights.

“I reckon I better go fust.” Cass explained. “I kin take keer of snakes and sech.” Glad enough to give him the right of way, Marvin and I fell in in single file behind the swinging light.

We had to walk fast to keep up with the lanky moonshiner. He led us unerringly up to what appeared to be a solid line of dense bushes, and we were right on top of them before I noticed that a narrow path offered a difficult passage through them. Something jumped out in the path once, sending my heart up into my throat. It was only a terrified rabbit, roused from his slumber in a brier patch. Marvin gave a startled glance over his shoulder, but neither of us spoke. I grinned to myself, taking comfort from the thought that he was just as scared as I was.

The path ran on about the length of two city blocks, then the bushes ended and I felt the ooze of soft ground under my feet. The lantern ahead lit up the butts of great cypress trees hundreds of years old. The light was reflected from dark stagnant water which looked as black and hard as polished iron. I looked up, but the matted branches overhead shut out even a glimpse of the stars. Cass had waded into the water without any hesitation. There was nothing for us to do but follow. I patted myself on the back for wearing my hunting boots, although they did not aid much in keeping my feet dry. I was thinking of moccasins, and the protection of the thick leather around my legs was comforting. It probably would not have done a bit of good against a pair of fangs had I actually stepped on a big one.

Several times I thought we were lost. Cass would stop at a fallen cypress tree which barred our way and hold the lantern up high as if searching for a hidden landmark. Then he would make a quick decision and start off—sometimes straight ahead—and sometimes in a course which seemed to be at right angles to the one we had been following. He did not need to worry about Marvin and me. We hung too close on his trail. I know if he had suddenly plunged into a river we would have been close behind.

I lost all track of time. We climbed over fallen trees. I extricated myself from hanging vines with thorns on them an inch long which tore me cruelly. I sank in mud up to my knees and felt that each attempt to pull out my tired legs would be my last. Marvin became a fiendish shadow ahead of me which never stopped and which I had to follow at all costs. We came to an abandoned tram road once used by a big lumber company which had logged in there. For an interminable length of time we walked ties. I fell down and bruised my knee badly, but I refused Marvin’s proffered assistance rather curtly, and was up again immediately stumbling on my way. I was glad when Cass took to the swamp again for it was easier going in the mud and water than on the old road bed.

Once Cass Rhodes stopped short and reached for the heavy gun which swung at his hip. Some large animal had crashed through the trees ahead of us splashing noisily through the water. Then with a laconic, “Cow I reckon!” he started on his way again. My imagination began to run riot. I conjured up pictures of panther and bear stalking us through the darkness. Then I became certain that I heard the soft plop-plop of padded feet some distance in back of me. I dismissed it from my mind but I instinctively moved up closer to Marvin. I know now that I had not been mistaken about being followed through that eerie swamp, but the matter left my mind with a rush at the time. Cass’s lantern was growing dimmer. Suddenly, with a final hiss, it went out entirely. We were left standing in a blackness so thick that even the faintest outline of the timber surrounding us was blotted out completely.

“Youall stay where you air until I git a match,” I heard Cass say. “Th’ daggown lamp’s done run out of gas.”

“What are we going to do?” I demanded petulantly. I felt that it was useless to ask, and that we faced the prospect of standing up in the swamp until daybreak. Cass’s next words reassured me.

“When I git a light youall come up and git aholt of my coat. ‘Taint fur to the hut. We shoulda seed the light afore now. I kin find the way easy, though, in the plumb dark.” Matches rattled in a box. Then one flared up and I saw that Cass and Marvin were much closer to me than I had thought. Marvin took hold of Cass’s coat and I took hold of Marvin’s, and in this fashion we started our slow march to the finish of our journey. I did not relish traversing that snake-infested ground in the pitch dark, but anything was better than inaction.

We must have covered a quarter of a mile. Cass had stopped only once to strike a match, and then had gone straight on led by his unerring sense of direction. I heard the ripple of water ahead. Cass stopped again.

“That’s Tiger Creek,” he said softly. “We’re right on the bank. I’m goin’ to signal to Red so don’ be skeered.” Despite his warning I was scared, for the uncanny hoot of an owl sounded so close to me that I thought the bird was right in front of my face. It was fully a minute before I realized that Cass had done the hooting. We waited, but there was no reply. Cass repeated the signal.

“Durn funny!” he said. “ ‘Taint right somehow. Red was agoin’ to leave a light and he ain’t answered. Hit ain’t right. I reckon we better hurry.”

We stumbled on through the darkness. Marvin and I still clinging to our guide. The going was much easier. I could hear the creek gurgling on our left. The trees had given way to palmetto bushes, and by the faint light of the stars I discerned the outlines of a small shack. Cass stopped again and cautiously called: “Red! Hit’s Cass with the doctah.” We waited expectantly. Again there was no reply. We pushed open the makeshift door and entered.

My nerves were very much on edge. I had had but a modicum of rest for four days, and I had not quite recovered from my gruesome discovery on Lake Louisa. The trip through the swamp which we had just finished had not improved matters in the least. I realize that it was with a feeling of relief that I entered that ramshackle cabin. Far as it was from civilization it represented the handiwork of man. It was really a welcome sight when such a short time before I had pictured myself spending the night wading around in water up to my knees. I was upset about Red not answering Cass’s signal, but I knew that patients with a high fever often slept very soundly. It was quite possible that he had not heard us at all.

A few embers glowed in a rude fireplace and dimly lit up the interior. I could see two rough chairs, a square table in the middle of the room, and two bunks, one over the other, built into the wall. A figure lay in the lower bunk partially concealed in the shadow. I recognized my patient by the gleam of the firelight on his red hair. The place was stuffy and close. Marvin put some more wood on the fire.

While Cass was fooling with a smoky oil lamp, I unhooked and threw open the one window in the room. I had brought a small medical kit with me in my pocket. I took it out and placed it on the table.

“Red,” I said softly. “It’s Doctor Ryan. How are you feeling, old fellow?” The figure did not move or reply. It was then that it dawned on me that I might be too late. I walked quickly over to the bunk and placed my hand on his forehead. It was warm, but I could detect no sound of the labored breathing which I would naturally expect with pneumonia, and I had made up my mind that Salmon had pneumonia, if Cass’ story was true.

“What is it, Doctor?” Marvin asked.

“I’m not sure—yet,” I replied. “I’m afraid we’re too late.”

I took my stethoscope from the kit on the table, walked back to the bunk and started to pull down the blanket. It was tightly wound around the sick man and tucked in under his feet. Part way down it stopped. I could move it no further. I searched around to find out what it had caught on. Just then Cass succeeded in getting the refractory lamp lit and by its light, which cleared away the shadows in the bunk, I saw what had happened. The haft of a large hunting knife was pinning the blanket down directly over Red Salmon’s heart. He had been stabbed to death.

6

Fate seemed to have selected me as the hub around which that tragic web of murder and crime was woven. For years my life had been uneventful and peaceful. An occasional trip north for a short course of study in one of the famous clinics was my greatest excitement. A rare case where all my skill was brought into play to save a patient was my antidote to boredom. The smashing strike of a bass, the comfort of a good book, or the thrill of a talking picture were my recreations. Then, without reason or logic, I stood silent before the work of a killer who knew no mercy. Twice within the period of a few days I was to be the first to gaze horrified on his victims. Both times I was to feel that had I been but a few short minutes earlier a life might have been saved. The first had been a banker, and my friend. The second, a rough moonshiner, whose greatest crime was defrauding the government of his country. But to me the second was far more horrible than the first. An assassin who could shoot down an unarmed man in broad daylight was venomous enough. There was no name for a fiend who could coldbloodedly stab a victim who was desperately ill and defenseless.

Why I felt so sure that one man must have been concerned in both murders I do not know. Only that our community was ordinarily so peaceful and law abiding. It is true that there had been other murders during my years of practice. But they were different. The few that had occurred had been crimes of passion, drunken brawls that had ended in a shooting. The crimes of large cities did not touch us. We lacked the wealth to attract the racketeer and the gangster. Two killings so close together could mean only one thing to me: A desperate menace to us all, in the person of a dangerous criminal, was roaming the county.

The three of us stood silent and awed before the figure which lay so still in the lower bunk. Cass took off his hat. I could hear his breath sharply sucked in between his teeth. His big fingers rested on the butt of his pistol. I felt that the law would never have to deal with the murderer if Cass Rhodes could pick up his trail. I gathered up my useless medical kit and packed it back in the case. I thought how impotent a physician becomes in the presence of death. There was nothing to do except leave things as we found them and wait for the authorities to act I was about to ask Cass if there was no easier way of getting back to Orange Crest when a soft footfall sounded outside the door. Cass’ gun flashed from the holster and he half turned, facing the entrance. A voice spoke outside the window.

“Put down the gun, Cass. Thar’s a thutty-thutty coverin’ yuh so don’t move.” Cass laid the pistol on the table. The door swung open and Pete Crossley entered the shack followed by Luke Pomeroy, an Assistant Deputy Sheriff. Luke stopped at the door holding a heavy rifle at his side.

“Sorry we had to trail you out, Doc,” Pete said with a grin. “But we had to find Red Salmon. Luke saw his Ford parked near the edge of town. We thought we’d come along. Nice trip, isn’t it?”

“Pete, you’re too late.”

“Too late?” He sobered instantly. “He’s gone—“ He glanced at the bunk inquiringly, then walked quickly over to it and pulled down the blanket with which I had covered Red’s face. He stepped back and stood looking at the dead man for a moment. He snapped his fingers impatiently.

“He was murdered,” I stated so calmly that I surprised myself. “Stabbed to death. We found him that way, Pete. I came out here to treat him. He wanted to talk to me and Marvin. Evidently he knew something—”

The Sheriff had taken off the top blanket while I was speaking and was gazing at the forbidding haft of the knife. He wheeled on Cass, his face contorted with violent rage.

“Damn it, Cass Rhodes,” he fairly shouted, “you’ll tell me what you know about this if I have to string you up by the thumbs. You know who did this! Come on, spill it. You’ll get nothing but hell by keeping a shut mouth with me. I’m going to send the dirty skunk to the chair if I have to turn this county inside out!”

Stolid as he was, Cass Rhodes shrank back from the fury in Pete’s voice. “I swear fore God, Sheriff, I dunno who killed Red. He ain’ neveh tol’ me nothin’. He say hit’s better I don’ know nothin’, and that the Sheriff’s office ain’ goin’ to believe him nohow. He done sent me for the doctah and Mistah Lee ‘cause he’s skeered youall goin’ to hang that shooting at the lake on him. He knowed who done that killin’ ‘cause he seed hit himself. The same hound’s done got him now, Mistah Crossley. He’ll git me too lessn I’se keerful, ‘cause he thinks I done heerd something from Red. Red was my friend, Sheriff, and I’ll be powe’ful lonely—”

Crossley had pulled himself together while the woodsman was speaking. He broke into Cass’s vehement protest, his voice friendly.

“I’m sorry, Cass. I’m acting like a fool. This whole business is driving me crazy. I’ve been thinking Red could throw some light on it. It never occurred to me that he might be in danger if he could. We should be looking around and not standing here jabbering. Can you fill that gasoline lantern and light it?”

“Yessuh.” Cass produced a small can of gasoline from under the bunk and took it outside the window to fill the lantern away from the open fire. While he was busy with his task Pete and I proceeded to the more unpleasant one of removing the knife. Pete carefully wrapped a handkerchief around the hilt in case any fingerprints might be found. He then started a systematic search of the dead man’s meager wardrobe. A box of thirty-eight caliber cartridges, a pair of pliers, and a small paper backed book on distilling were the only rewards. A cupboard in the corner of the room occupied Marvin Lee and Pomeroy. It yielded an unloaded thirty-eight six shooter which accounted for the cartridges, and a pump shotgun. Crossley examined the latter with interest-It proved to be a 20 gauge. It was carefully oiled and cleaned so it was impossible to determine whether or not it had been recently fired. A half-box of shells was found which fitted it. They were all number eights—a quail load. It appeared that Red had not anticipated any trouble. Neither of his weapons was loaded, and they were only of the type which might be found in the house of anyone living far out in the Florida woods. The leather sheath, for the hunting knife which had caused his death, was found under the table. Pete also wrapped it in a cloth and slipped it in his pocket.

A light outside the window announced that Cass had put the powerful wind-proof lantern into service again. Pete asked Pomeroy to continue the search of the shack. Marvin and I, glad of the chance to get out in the air, went out with the Sheriff to be of what assistance we could.

The small house stood in a clearing about sixty feet square. The swift waters of Tiger Creek rippled at the back. The fastness of Tiger Swamp guarded the front. There was only one means of approach by land, the way we had taken through the swamp. It was an ideal hideaway, carefully chosen by a man who had spent his life in the wilds. It was very improbable that anyo

ne would stumble on such a place by accident. It was inconceivable that anyone without a thorough knowledge of Manasaw County could find it at all. One thing was certain. The Sheriff’s office would have to search for a murderer who knew that part of the State like a wild turkey. No casual stranger to the territory surrounding our town had crept up in the night to stab Red Salmon. At the first suspicion that the law was close to him the man Crossley was seeking could hide himself indefinitely.

The ground in front of the cabin was high and sandy. It was hopeless looking there. The way we had come, through the palmettos, was just as discouraging. The other side of the house presented a tangled morass. A rabbit could hardly have penetrated into it. Our only hope of a clue lay in the twenty feet separating the back of the house from the creek. There the ground was softer. It sloped down to black mud on the bank. Pete asked Marvin and me to wait while he and Cass investigated. We stood still and watched the light bobbing along close to the ground. Even the woodcraft of Cass Rhodes failed to detect so much as a footprint. It was Cass, however, who found the only trace left by the clever criminal. While it was not much still it served to show us how he had come and gone.

A narrow footpath led from the house to the stream. It had been tramped down hard by the carrying of many buckets of water. It also served as a runway for numerous semi-wild hogs which roamed the swamp at large. Cass and the Sheriff had gone over it first without result. Failing to find anything in the wet ground they decided to make a second and more careful survey of the path. We heard Pete call from the bank and ran down to join them. Pete held the lantern close to the ground and pointed. There was a sharp V-shaped indentation in the muddy bank.

“Cass found it,” Pete said. “A boat’s been here. Recently too. Where does Tiger Creek lead to, Cass?”

Blood on Lake Louisa

Blood on Lake Louisa