- Home

- Baynard H. Kendrick

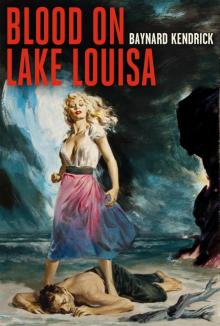

Blood on Lake Louisa Page 7

Blood on Lake Louisa Read online

Page 7

“Much luck?”

“I didn’t have much at first, because I didn’t know the country very well. I did pretty well toward the end of the season. Got twelve birds on the last day.”

“Where did you go?”

Bartlett grinned. “I’m really not sure where I went. You see I followed Tim Reig. He took me on quite a trip out State Road No. 2.1 stayed away from him, for I didn’t want him to see me, but I could hear him shooting.”

“Were you near him all day?”

“Yes. I followed him home. It was dark when I got in.”

“Thanks, Mr. Bartlett. There’s nothing else, unless Mr. Crossley has something he wants to ask.”

“Nothing more, Harry,” Pete said. “Good night, and thanks.”

“So the Spence-Bartlett-Reig trail ends at ‘Possum Farm,” Marvin remarked after Bartlett had gone. “A lot of information you got out of that trio, Sanderson.”

The State’s Attorney sat down for the first time during the evening. “Only, that if they’re all telling the truth, none of them could have had anything to do with the murder. It shouldn’t be hard to check their stories.”

“I can check part of them right now,” Pete declared. He shouted a lusty “Ed!” The Deputy stepped into the room.

“Did you hear what Reig and Bartlett had to say?”

“Sure. Reig’s story is O. K. I’ve been out with him to the ‘Possum Farm. He asked me to go again a couple of days before the season closed, but I couldn’t get away. I don’t know about Bartlett, but he talks straight.”

“And that’s that,” I remarked. “Forman was in his jewelry store, and Bartlett, and Reig, were fifty miles from Lake Louisa when the murder was committed. Where does the trail lead now?”

“Home and to bed for me.” Marvin rose and stretched himself. “You coming, Doc?”

Pete caught my eye and shook his head almost imperceptibly. “No,” I said. “I have a call to make at eleven-thirty. I think I’ll stay and make Pete entertain me until then.” We walked to the door with Marvin, and watched him until he drove away. When we returned to the room I looked at the Sheriff inquiringly.

“I want your help, Doc.” He knocked his pipe out on the edge of the fireplace. “I hate to ask you to give any more of your time. I know you’re busy and—”

“Rot! What do you want me to do?”

“I want you to go out to Louisa with Ed, and show him exactly where you were when you fired at those ducks. We have decided that it is advisable to check over the scene of the shooting again. I have to leave town with Carl for a couple of days, or I would go with you. I’ve hesitated to ask you for I know how distasteful—”

“When do you want me to go?”

“Tomorrow, if you can. The sooner the better.”

“If Ed will stop by for me at six tomorrow morning, I’ll be ready. I have to be back by noon though. I have an appointment.”

“That’s splendid of you, Doctor,” Sanderson boomed at me. “I wish we could get such help from everybody.”

“You hear, Ed,” Pete warned the Deputy. “Be sure that Doc gets back by noon.”

“That’ll give us loads of time, Sheriff. You’ll be ready, won’t you, Doctor? I’ll be at your house at six.”

Pete walked out on the porch with me as I was leaving. He held my hand for a moment in his firm clasp as he wished me a good night.

“You’re being awfully decent, Doc. I’ll remember it.”

“Forget it. I’m mixed up in this too.”

“If you have time, I wish you’d take a look around and give Ed a hand in trying to find something. He’s been over the ground once. You may see something we have missed. If you happen to find anything, no matter how unimportant it may seem, keep it for me until I get back.”

“Don’t worry,” I assured him. “If I find anything, I’ll make sure that you get it It would tickle me pink to find something you fellows missed.”

I did find something, but I was not tickled pink. I was nearly killed trying to keep my promise to deliver it to Pete Crossley.

10

It was not quite daylight when I woke the next morning. I dressed hurriedly, glad to get into my warm hunting clothes for the weather was raw and cold. I scarcely had time to finish a second cup of coffee when I heard Ed Brown blowing his horn for me in front of the house. When I stepped out on the porch to tell him I would be ready in a few minutes I found that I could not see ten feet in front of me. A white cotton-like fog pressed closely around me, completely hiding from view the automobile which stood at the curb. Only two weird yellow globes of light gave any indication as to its location.

The Deputy refused my invitation to have a cup of coffee before starting, so I went back in the house, turned off the lights, and quickly rejoined him. Once in the sedan, I felt entirely cut off from the rest of the world. Windshield and windows were thickly clouded. Peering ahead through the half-moons kept clear by the busily working wipers I saw that the headlights were dim and ineffectual. There was not a breath of air stirring, and the fog clung close to the ground. The most powerful searchlight would have been futile against such a blanket. Ed made good time. He drove skilfully and quickly over the familiar road. His speed was far greater than I would have dared to attempt under similar circumstances.

“Looks like we’re in for this all morning,” he remarked. “If the sun comes up it may lift, but I think it’s going to be cloudy.”

“It’s going to be pretty difficult to do any searching, isn’t it?”

“I guess so, Doc. But I don’t think it will make much difference anyhow. We’ve been over that ground with everything but a magnifying glass.”

“You didn’t find anything in the Simmons house?”

“Nothing but rubbish. Nobody has lived in it for years. Sometimes a fisherman will spend the night there if the weather is bad, but I wouldn’t want to.”

“Why?”

“Oh, I just don’t like old houses.” He twisted the wheel over and gave me a bad moment as he deftly dodged a farm wagon which had been carelessly left on the side of the road. “You can have the pleasure of searching it this morning if you like. Have you ever been in it?”

“No. I’ve always been too busy fishing. That’s the only thing that brings me to Lake Louisa.”

Our talk turned to bass, and the many lakes which abounded in our County. Daylight came, and with it a light breeze which rolled the fog along the road like giant snowballs. There would be a short stretch where we could see clearly, but we would immediately enter another bank with zero visibility. Ed told me of a small unnamed lake which he had heard was teeming with fish, and I made him promise to take me there at the first opportunity. The fog became thicker and thicker. Before I realized it the car had stopped in the clearing where I had entered the rowboat with Buddy Nixon just a week before.

The breeze had died out again. Everything was ghostly white and deathly still. I strained my ears but I could not hear even the soft lapping of the lake against the shore. Every blade of grass and twig underfoot was covered with hoar frost which crunched loudly as we walked down to the boat. We left a trail of footprints as clearly as if we had walked through flour—footprints which would disappear at the first touch of sun. We pushed through the reeds, and were instantly cut off from any sight of the shore. The fog hung about a foot above the placid surface of the water, reaching down now and again to hold to it with spectral tentacles. Ed set to work with the oars and rowed vigorously until we reached the sparse grass which indicated we were close to the inside shore of the west fork. He turned the boat sharply south and, guided by occasional glimpses of the shore line, headed for that shallow portion at the south end known as the Cow Pasture.

“It would be quicker if I could head straight down the lake, Doc. But there’s no telling where we’d end up in this fog,” he explained. “You keep your eyes peeled and when we get down a ways I’ll keep as close in as I can. I’d like to land at the same place you did if it’s possi

ble.”

“I’ll do my best,” I promised him. “If I can’t find the place from the boat, I think I’ll know it when we get on shore. The bank slopes up rather steeply right where I shot at the ducks.”

The fog thinned out a bit as we neared the south end of the lake. Ed was rowing as close to the bank as he could get. Occasionally I could glimpse the trees which grew closest to the water. We rounded a point which I judged to be the one that ordinarily cut off the view of the old Simmons dock. If my surmise was correct we were right off the spot where I had found the banker’s body.

“Pull her in here, Ed,” I directed. “This is about as close as I can judge it. I fired just as Buddy pulled around a point of land. I remember seeing the dock just ahead.”

“Well this is the same place then.” He gave a few more strokes which ran us into the grass. “We can land right here. Pete wants me to pace off the distance from the lake to where we found Mitchell’s gun.”

“What had I better do?”

We pulled the boat half out of water before he answered. “Walk around the edge of the lake to the old dock. If you don’t find anything see what you can unearth in the house. I’m going to have a look around in the grove at the back. I’ll join you in the house later.”

“I really don’t know what I’m looking for,” I admitted. “What do you think Pete expects us to find?”

“Nothing at all.” He took a package of cigarettes from his pocket, offered me one and lit one himself. “I’ve been over the house and the ground in front. Pete figured it wouldn’t do any harm to have another person look things over as long as you were coming out The main thing he wanted checked was where you found the body.”

He strode off up the slope and was swallowed in the fog. I started walking slowly along the bank imbued with all the eagerness of the amateur detective on the trail of clues. I poked into every bush and turned over every clod of earth which I felt might conceal anything of importance. I found an old log which was partly burned and a few empty tins, but grass had grown up where the fire had been and the tins were red and indistinguishable with rust. The dock yielded nothing. I lifted up a couple of boards which were loose and discovered there was a small space between them and the beams. Determined to overlook nothing I waded out underneath the dock and ran my fingers the entire length of the space. It was empty.

As the morning wore on the fog began to lift. When my search of the dock was ended the outlines of the Simmons house were visible. There was evidence that Arnold Simmons had made an attempt to beautify his place for I followed an old path bordered with conch shells up to the front steps. All the large trees which might have interfered had been cut down to give an uninterrupted view of the lake from the front porch. Barring the inconvenience of transportation I could not imagine a more ideal location for a home.

The house was built on sloping ground, and was supported by a foundation of rough stones mortared together to form a solid wall which ran all the way around the building. It was exceptionally well constructed for an old Florida house, and must have cost its owner a lot of money. There were no rocks in the vicinity such as were used in the foundation. I remember wondering what had prompted Simmons to go to the expense of having them hauled in to a place where timber was so plentiful. It was true that the solid wall foundation served to keep out wandering animals that delight in making a home under a farmhouse, but a wooden lattice would have served the same purpose.

The steps which led up to the porch were badly rotted. I ascended them gingerly. I was rather surprised to find the verandah in good condition. It extended across the front of the house, and part way down the west side. At the end was a closed and bolted door, which I later found led into the kitchen. The porch had once been entirely screened against mosquitoes, but only a few dots of rusty screen wire held by tack heads bore witness to the fact. There were two windows opening out onto the side porch, but the glass was filthy with the accumulated dirt of years, and I could see nothing when I tried to look inside. I met with no better success with the two which opened onto the front porch—one on each side of the double front door. Two panes were missing from one of the sash, but the openings had been boarded up with ends from an orange box. I gave up trying to look inside, and tried the front door. It was unlocked. Rather hesitantly, feeling as though I were intruding upon a long dead past, I pushed it open and entered.

A wisp of white fog followed me in. I closed the door behind me and stood still for a moment until my eyes accustomed themselves to the gloom of the chilly hall. To the left a flight of narrow stairs led to the second floor. At the foot of the stairs a door opened into one of the rooms I had tried to look into from the porch. A similar door at my right hand led into the other room. I walked to the end of the hall and found myself in a large room which covered two thirds of the back of the house. Evidently it had been used els a general living room and dining room. A huge old fashioned stone fireplace covered almost the entire wall which formed the back of the house. There were three windows—one on each side of the fireplace, and one at the east end of the room. The one to the left of the fireplace had a broken pane at the bottom. A door at the west end led into the kitchen I had tried to enter from the porch. The two small rooms on each side of the hall, the large room at the back, and the kitchen, constituted the entire downstairs.

It did not look very promising. There was the usual litter found in any old house to which people have access. A broken lamp chimney was on the mantelpiece. A chipped white plate and a teacup without a handle—both black with grime—lay on the hearth. A calendar—1903— displayed the buxom charms of a picture-hatted lady using a face cream. Hat and lady were both very much fly specked. There was a single piece of furniture in the room—a cheap cane bottom chair. The cane bottom was missing, but the hole had been covered with newspapers offering a makeshift resting place.

I turned my attention to the kitchen. An old iron sink stood in one corner surmounted by a cobwebbed pump. I could not resist the impulse to try it, and it shrieked at me vilely for my pains. The flue in the wall contained nothing but soot. Thoroughly begrimed, I left the kitchen and tried the two front rooms. They were absolutely bare. I tested the floors for loose boards but the house had been built when lumber cost but a pittance, and nails were cheap. The floors were as solid as the day they were laid. Tired and disappointed I climbed the stairs to the second floor.

There were four small rooms upstairs, and I searched every inch of them. I was thoroughly annoyed at my inability to find anything of interest. One of the rooms had been papered in flamboyant roses and I poked around until I discovered a flue which I figured should be there. I was cheered up for a moment, but my spirits drooped when I only uncovered more soot. There was a broken down bureau in one of the back rooms, and I unearthed from a drawer a faded text which read: “Prepare to meet thy Maker!” It depressed me still further. Then I went downstairs again and blundered right on to the discovery which nearly cost me my life.

The penetrating cold, peculiar to uninhabited houses, had chilled me through, and I was in hopes Ed Brown would hurry. I went out on the porch and called to him, but received no reply. I decided to make myself comfortable until he came. There was lots of wood around the front steps, and I gathered an armful and carried it into the big room at the back of the house. I started to lay a fire, then remembered that I had neglected to search up the chimney. The fireplace was large enough for me to get inside if I crouched. Once in it, I found that I could almost stand up straight. I struck several matches, but the only thing I saw was the jagged soot-blackened ends of the rocks. The flue slanted up toward the back of the chimney. I stretched my arm in as far as it would go and groped around. Satisfied that there was nothing there, I returned to the room, grimier than ever.

The wood which I had carried in was damp, so I moved the bottomless chair up in front of the fireplace, and picked up the top newspaper off the seat to start my fire. It was a Miami morning paper, The Floridian, folded to quarter

page size. As I unfolded it a heading caught my attention:

NIMRODS WARNED BY

COMMISSIONER

Open Season Closes Today

I glanced at the date line and saw that it was dated Wednesday, February 15th—the day David Mitchell was killed.

11

There was nothing particularly unusual about finding a copy of the Miami Floridian in the Simmons house. Both newsdealers in Orange Crest received them daily on the early morning train, and a number of people in the town were subscribers. On the fifteenth the woods had been full of hunters. Buddy Nixon had told me that cars were passing his house from before daylight until late in the afternoon. Any one of a great many people might have stopped to eat breakfast or lunch in the deserted Simmons place, and left the paper behind them. Nevertheless, I felt that I had made a momentous discovery. I could readily understand how the Sheriff’s office could have overlooked the paper. The house had been searched merely as a matter of routine. There was really nothing tangible to connect the vacant residence with the crime. Even with the close search I had made I would not have noticed the daily if the item about the hunters had not attracted my attention.

Prompted more by curiosity than anything else I started to look through the paper. On the third page there was an advertisement for a Miami real estate development with an ample margin of blank space around it. Written in the margin of the ad, with a soft lead pencil, in an uneducated scrawl were the following figures:

I copied them down when I arrived home that night so I know they are correct. They meant nothing to me at the time. If I could have been sure who wrote them, and what they meant, I would have guarded them more carefully than I did. As it was, when we found out their real significance it was too late to do anything about it.

I refolded the paper, slipped it into the capacious pocket of my hunting jacket, and turned my attention to the others on the chair. The one which I picked up had been lying loosely on the top. The others were wedged down in the opening of the seat as if they had been sat on many times. I lifted them out carefully so as not to tear them. They were grimy and dirty around the edges, but fairly clean inside. There were fourteen more, all Miami Floridians. As I glanced at the dates I received the biggest thrill of my life. There was a single paper for every month for the past fourteen months, and every one of them bore the date of the fifteenth.

Blood on Lake Louisa

Blood on Lake Louisa